Here’s a neat scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) paper from the 15th by Yin et al. titled “Negative flatband magnetism in a spin-orbit coupled kagome magnet”.

There’s a lot to unpack in the title (again) but most of it can be ignored (again). That’s the beauty of buzzwords.

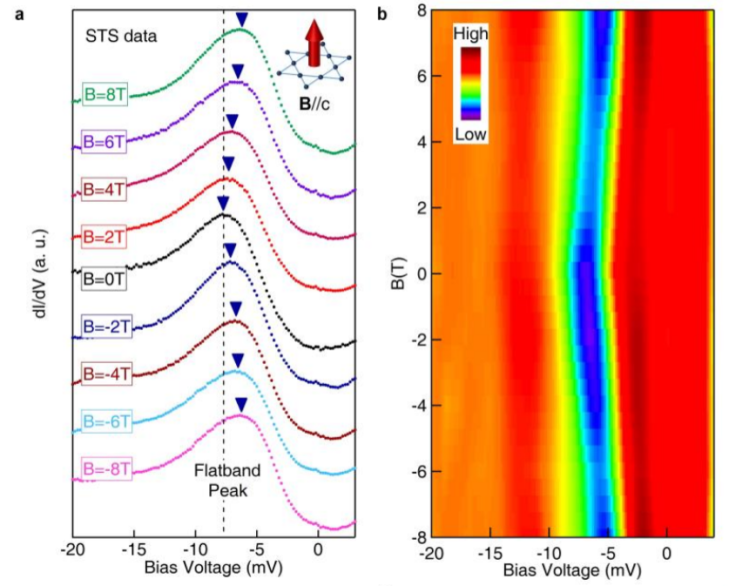

It’s a long abstract but the key points are: 1) the material is a ‘kagome’ magnet Co3Sn2S2. 2) they measure a (flatband) peak in the electron density of states 3) this peak doesn’t shift in energy the way you expect it to when there’s a magnetic field.

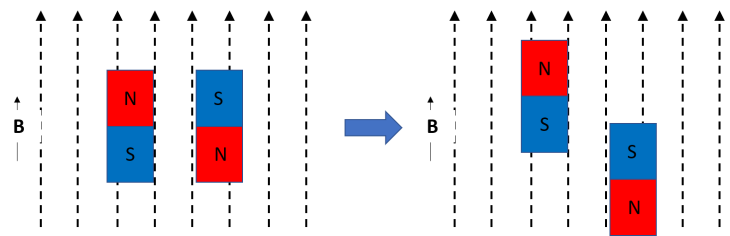

The last point is probably the coolest. Imagine a bar magnet with a north and south pole. If you put near another magnet that’s generating a magnetic field, it’ll either move towards or away from it. Now, put another bar magnet next to the first, except flip it. If you turn on the magnetic field again, one of those magnets is going to move toward the source, and one is going to move away. This is because it’s more energetically favourable (try to pull a magnet off the fridge – it takes energy. it’s more energetically favourable to stick to the fridge.)

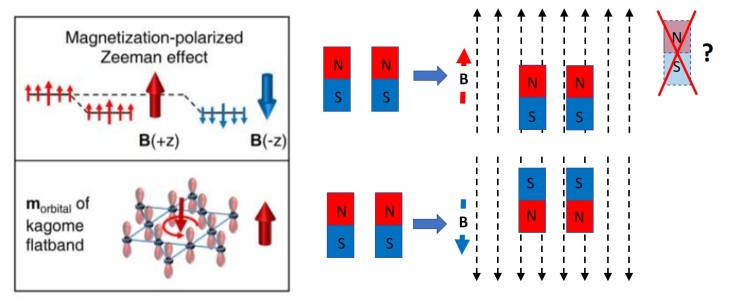

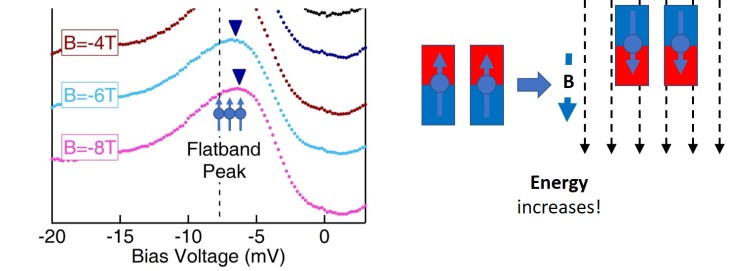

This is similar to what’s in Fig. 4g of the paper – except, notice that no matter if the magnetic field (B) is pointing up or down, the spins (like the bar magnet in the example) both move the same way. Which is definitely not what you would expect, and definitely doesn’t happen in most materials.

And on top of that, notice that while you would expect the magnet pointing North to move up when the field is pointing up, it actually moves down! (This isn’t a perfect match with Fig 4g on the left, where going ‘down’ in energy is equivalent to the bar magnet moving physically up. Lower energy = more favourable, like a fridge magnet trying to stay stuck to the fridge.) Instead of going where it should go (up) it’s going away from where it should go (down) in a direction that increases energy instead. To understand why, we have to look a little deeper into this material itself, and the way the atoms are arranged.

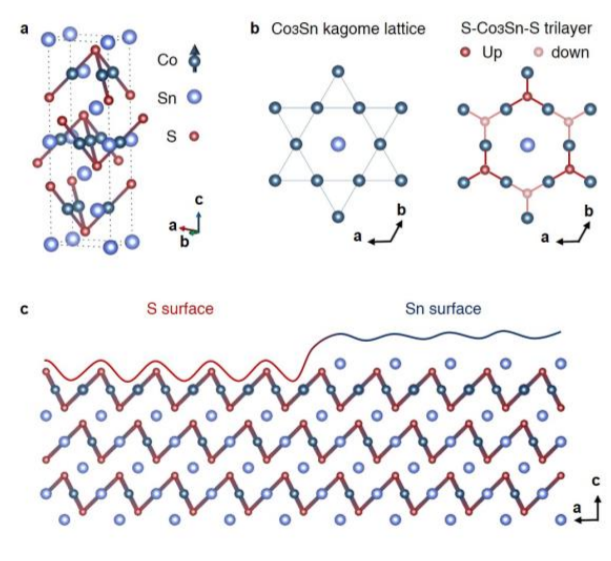

This material, Co3Sn2S2 is made up of two sorts of layers. The Co3Sn ‘kagome’ layer where the Co atoms form a kagome shape (like a Star of David, see below for a long aside.), has a Sn atom in the middle of each hexagon, and then is sandwiched between a layer of S atoms. The other layer is only Sn atoms. What they did here is ‘cleave’ the sample by breaking off the top surface of a piece of crystal, by gluing a small pin to the top of it and then hitting the pin. Since there’s two types of surfaces (ones with S atoms and ones with Sn atoms), either surface could be exposed.

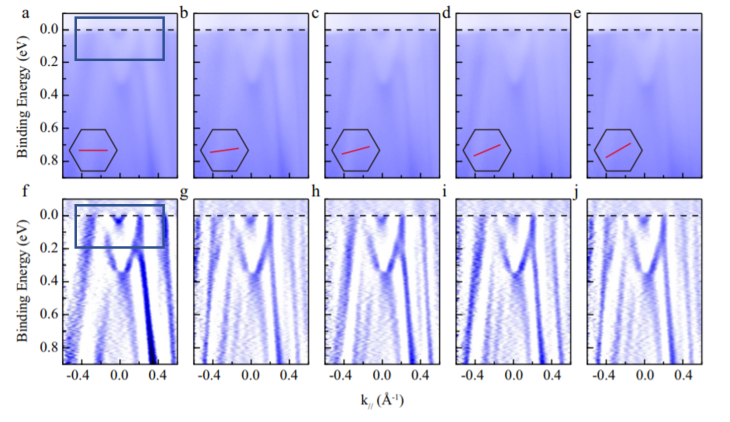

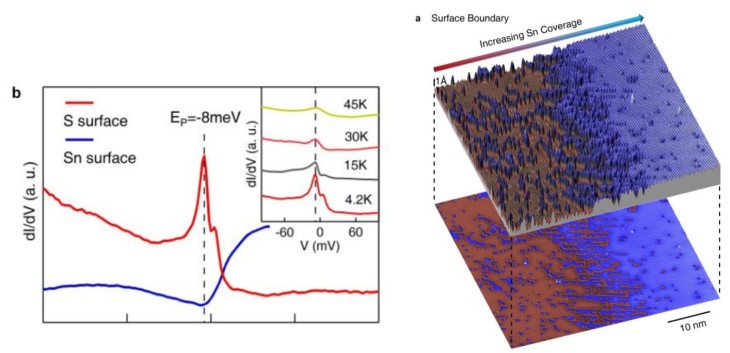

Unlike the previous paper discussed that used a technique called angle resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES), this paper uses a technique called scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM). Two main differences is that ARPES looks directly at the band structure but averaged over a large area, while STM indirectly measures the band structure but at a single atomic point. This means that unlike ARPES, STM can tell exactly which surface is being measured, which is important in this case because it’s different.

What they found is that there’s a peak in the density of states (a description of the electronic structure of the material) that exists only on the S surface, and not on the Sn surface. (I invite you to read the paper for further details.) Peaks are exciting! They can mean lots of things, but more importantly, you can manipulate the sample by changing the temperature, applying a magnetic field, applying an electric field, moving the sample, rotating the sample, etc. and see what happens to a peak. (It’s hard to see what happens to a featureless signal, because a featureless signal will probably remain featureless.)

Excitingly enough, something does happen to this S surface only peak. Imagine the peak being filled by a bunch of electrons with spins all pointing one way (again, you can think of them as tiny bar magnets, but don’t tell your physics teacher I said that.)

Now, when they applied a magnetic field up, they found that all these electrons increased in energy–and then when the magnetic field was applied down, they increased in energy by the same amount.

This is because there is a “flat band” that contributes to that peak, that has a different sort of magnetism (“orbital magnetism”) that’s negative of the ferromagnetic magnetism (the magnetism we usually think of when we think of magnets). Systems with flat bands are rare, and kagome systems are one of the very few systems that can have flat bands. So here, there’s evidence that this material does have a flat band, and more importantly, it’s near the Fermi level–or the energy where experiments can actually measure.

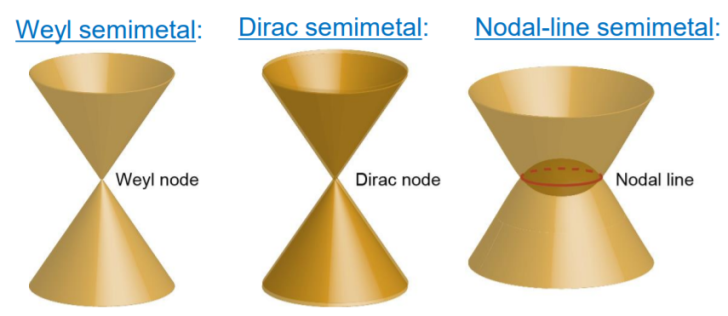

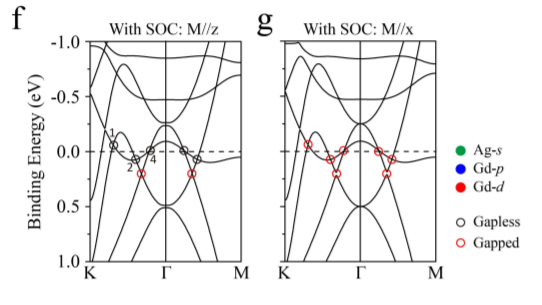

The orbital magnetism and flat band tie into some topological physics (this material’s attracted a lot of attention because it’s theoretically a Weyl semimetal), which also makes it extremely interesting from a theoretical point of view.

And again, here’s the paper for those who want to look at the figures in the original context!

—

And, some more elaboration on kagome lattices:

<img

<img